Up the creek where the sunset is real!

A few weeks ago, I was driven up the creek; the Yarriambiack Creek to be precise. Doug, a farmer who had retired into Hopetoun, a dwindling town in Victoria’s Mallee, was showing me the love of his life. “We really care about this creek and it’s important to our town, it’s a bloody shame to see it like this.”

“Like this” is a creek bed both dry and sere, edged by gnarled gum-trees nearly looking limp. “We are in drought, and there’s little anyone can do about that, but when there is water, the Yarriambiack Creek people don’t want to see it diverted into other streams and channels, we just want our fair share.” growls Doug.

That’s why I was being driven up the creek – to hear, first-hand, the history of the creek; where the water flows out of the creek bed and onto surrounding land when “a fair flush comes down”; where the floods of ‘56 and ‘64 reached; when invasive weeds first appeared.

Doug is a creekkeeper, the Yarriambiack Creekkeeper, a member of Waterkeepers Australia. He clearly loves the creek and he is keen to share that love with others. He is now doing the rounds of the schools up and down the Yarriambiack to build the next generation of creekkeeping.

Aha, you say – schools are on about curriculum, not creekkeeping. But this is Doug’s cunning, he talks about using school stuff (he doesn’t say “curriculum”) to help the kids with what that they need to know to look after their creek. They might start with looking at the amount of water in the creek using historical data; they take samples and measure for nitrates, phosphates, dissolved oxygen; they find old-timers who fished it in a run of good years and ask them what lived there. Creative students might search out Major Sir Thomas Mitchell’s diary records of the near-by district as he passed through, others might seek information about the indigenous people and the rock art at the western end of the Grampians.

Now the creek is flowing into the curriculum as students submit designs for the Yarriambiack Creek Committee logo, they design the marketing brochure, others write media releases about forthcoming meetings and community river projects. Now the school is also flowing into the community as their interests coincide, albeit driven from different but nonetheless complementary aims – creekkeeping and curriculum.

I work for Waterkeepers Australia, and I find Dougs and the students that Doug is working with everywhere. I don’t think it took the recent national push for Civics and Citizenship Education to start this, it was happening in many places, but the push legitimized it. When many of us started out as environmental educators in the early 70s, we were told to keep our environmental views to ourselves. We matured professionally and learned to put arguments into curriculum contexts, while the community at large realized that to engage kids in learning, they had to accept that kids would take on the contexts that were real to them and the communities in which they lived and build them into curriculum.

We don’t have to argue any more that schools should be involved in environmental monitoring, in community engagement and in taking part in community decision- making. It has become so much part of mainstream thinking that many schools, particularly in the private sector but now in such government sector schools as Victoria’s Alpine School at Mt Hotham, are abandoning their middle-year text books in favour of a concept curriculum (Well, we had concept albums!) that focus on community involvement, personal development and real-life activities.

In NSW, many schools in the Murray Darling Basin have been involved in the youth leadership programs conducted by Oz GREEN. Sue and Col Lennox started Oz GREEN in the early ‘90s when their science students living along Sydney’s northern beaches reckoned that working out why their favourite surfing spots now made them sick was more important than doing titrations to make liquids change colour. The learning programs that ensued, before Sue and Col left formal teaching and started real teaching, have now led to thousands of students knowing – really knowing – about salinity and other water quality issues in the Murray, the Murrumbidgee and the Darling.

In SA, the Youth Environment Council is conducted as a partnership between the Departments of Education and Environment. Many students have passed through this long-standing program and there is a strong cadre of skilled informed advocates for a better environment in SA as a result. Ask David Butler or Jo Bishop, the culprits behind the Alliance, about the pitfalls of working outside schools, or Oz GREEN’s Sue and Col about the highs and lows of working in the community, as gloriously random and as haphazard as it is, and they will tell you that pitfalls and lows are aplenty. But they’ll also tell you how enriching it is. Kids working in communities, tapping into the realities of personality, local politics, budget constraints, timelines – this is not vicarious learning. Kids working with community leaders, kids being community leaders, kids bringing about real change, breaking a big story, having an interview published – this is what fires them up and keeps them going and it links their ‘book learning’ with their community learning.

Now back to Waterkeepers Australia. Our national organization works with community groups rather than schools. The groups that we support must be incorporated, for then we can make some assumptions that their governance is sound, that they have access to funding programs and they won’t abscond with the bank balance to tropical islands. We can help with building their infrastructure, we can assist with access to expert knowledge and the latest research and we can work with them to build their skills base, including how to work with their local schools and run public education programs. What we are doing, and the communities with which we are working, can be found on the website www.waterkeepers.org.au .

We are looking for the Dougs and the communities where the Dougs live, to work with, for the Yarriambiack isn’t the only creek in trouble. But further, we don’t just want to find communities where there is a waterway in trouble – let’s get to work before that happens. There are many stories of successful school-community partnerships that are into preventative care and that’s much easier than restoration.

A soundly-based community group works right across its community – and that means working with the local schools. For the community group, there is the opportunity to magnify their effectiveness, for a school provides an efficient means for disseminating community information, a school holds publicly-purchased equipment for environmental monitoring and its teachers and students have the skills to manage and interpret data. A school can become a centre for community leadership in environmental improvement, as students gather data and contribute through brochures, newsletter and displays to raise the level of community knowledge and involve their community on real issues.

And for the school – through a school-community partnership they can involve their students in the real world. They can build partnerships with local private businesses, with the resource contributions that they might bring, and give their students direct experience. Learning is not an abstract, academic exercise pursued for its own sake and totally independent of the community in which it occurs. It is a bridge into the community and it is preparation for active participation in that community. It should be real!

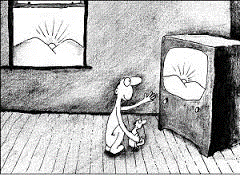

Many years ago cartoonist Michael Leunig drew an adult and child watching a sunset on TV, while outside the real sunset was taking place. Our kids should be able to see the real sunset.

Links

Oz GREEN www.ozgreen.org.au

Youth Environment Council http://www.environment.sa.gov.au/sustainability/education.html#YEC