Night parrot found to have poor vision, keeps running into things in the dark

Kemii Maguire

ABC North West Qld

12 June 2020

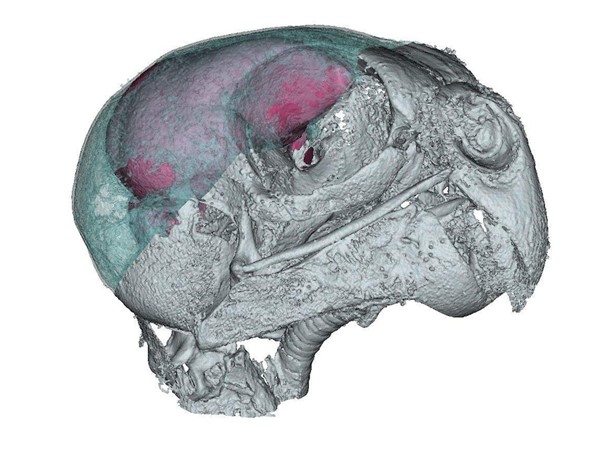

Night parrots have similar eye size to other parrots, with smaller optic nerves and lobes that provide less resolution. Supplied: Flinders University

Australia’s elusive night parrot may be in decline because the species has trouble seeing in the dark, a team of researchers has found.

The night parrot is one of only two nocturnal parrot species in the world, and is an endangered species living in small numbers across outback Australia.

Flinders University researchers discovered an issue with the night parrot’s eyesight after analysing a 3D reconstruction of the bird’s skull.

Computer tomography (CT) scans of an intact night parrot specimen were compared with other bird skulls, showing its eye size, optic nerves and lobes were similar to, and in some cases smaller than, those of diurnal (daytime) parrots.

Co-leader of the research team, Vera Weisbecker, said the issue with the night parrot’s eyesight was resolution.

“It had the same eye diameter as other normal parrots, but it seems to be able to see with less acuity,” Dr Weisbecker said.

She said while the night parrot differed from other nocturnal Australian birds, including the tawny frogmouth, its lack of sight was similar to the other nocturnal parrot — the large kakapo in New Zealand.

The night parrot’s ability to fly, however, has stumped researchers.

“The kakapo parrot has lost its ability to fly and hops on the ground, whereas the night parrot still flies, and there lies the problem of the bird running into things,” Dr Weisbecker said.

Flinders University researchers have been comparing the night parrot with other nocturnal animals. Supplied: Flinders University

Findings help explain behaviour

Nick Leseberg works with the nocturnal native at the University of Queensland. The PhD candidate said the night parrot’s bad eyesight explained his observations in outback Queensland.

“It always puzzled me that there are owls that live in the forest and they can fly around trees, but the night parrot seemed to live in such open plain spinifex,” he said.

“It made me wonder, maybe the night parrot’s vision isn’t as good as we thought.”

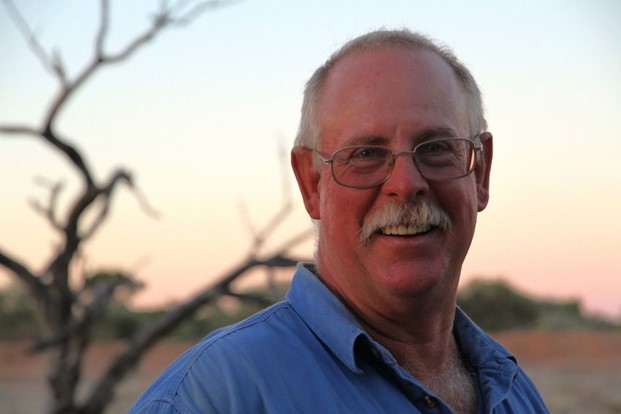

Nick Leseberg at Pullen Pullen Reserve. ABC Science: Ann Jones

Fencing a key to survival

The Flinders University study also suggested that fencing was a factor in the species’ decline.

“We know already that a lot of birds that are active at dusk and dawn have trouble with fencing,” Dr Weisbecker said.

“There’s been one decapitated specimen in the Diamantina National Park, but there are a lot of other nocturnal birds that

[strike]

fences.”

Angus Emmott, the owner of Noonbah Station, south-east of where the decapitated night parrot was found, agreed that fencing was a problem for flying animals.

But the avid naturalist said he believed feral dog fencing was not a problem surrounding the Diamantina National Park, and removing fencing was not going to make night flying safer for the parrot.

“Out where night parrots exist, I don’t think there would be much feral dog exclusion fencing to worry about,” Mr Emmott said.

“I think all we can do, like in some areas of Western Australia, is put a highly visible tape on the top wire of the fence.”

Mr Emmott says eradicating fencing across Western Queensland will not help the night parrot’s survival. ABC Open: Gemma Deavin

Parrot’s controversial past

The night parrot was the subject of controversial research last year when a panel of ornithologists and conservation scientists deemed an amateur recording of night parrots in 2013 was fake.

The deception created scepticism about what was thought to be known of the species.

Dr Weisbecker said that transparency in the Flinders University study would go some way to ensure trust in the findings.

Queensland Museum had what was believed to be the only intact skull of the elusive night parrot. Supplied: Flinders University

“At the time that [the bird] was CT scanned, it was the only specimen that we knew had a complete skull,” she said.

“All our 3D reconstructions of this bird and any other birds we compared are in a publicly accessible repository, so anyone who wants to check our measurements can do so.

“If anyone wants to use the 3D reconstruction and make a keyring out of it, they also can.”

Mr Leseberg was also worried last year’s controversy may discredit future studies.

He said the controversy surrounded one or two night parrot sightings, whereas other observations had found up to six areas the night parrot inhabited across Australia.

“If people latch onto that controversy, they might think that it’s all rubbish,” he said.

“It shows how important some of that lab research can be to filling in the gaps for a certain species.”

Meanwhile, scans of the night parrot skull have inspired an additional study into other bird brain structures at Flinders University.

“We thought we’d expand this to other nocturnal — or dark-active — Australian birds and are still working on that at the moment,” Dr Weisbecker said.