Night parrots, slothful dreaming and our Diamantina trip

My old school song, sung lustily by we small boys at Shepparton High School, supplied me with many words of inspiration, including :

“No thing of worth is won by slothful

dreaming

The path to fame is lit by midnight oil.”

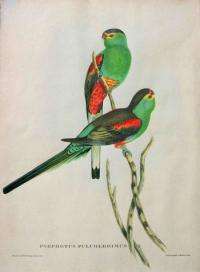

Alright, I was a particular kind of nerd, and a birds’ egg collector at that. My involvement in the environment sector for almost all of my adult life has been by way of doing penance for my errant youth. What I have kept into my adult life has been a keen appreciation of birds, bird distribution and bird behaviour, including nesting behaviour. As a self-confessed nerd, I’m also a bit of a pedant, quite taken with words and their meaning. These interests have their confluence in considering the now extinct Paradise parrot.

Psephotus pulcherrimus

What was the impact of egg-collecting (oology) on the decline of the species that was suffering serious habitat loss as the Darling Downs were cleared for grazing? Their distribution was quite limited and the ant-hills in which they nested stood in the way of farming practice. So Psephotus pulcherrimus has not been seen since the 1920s. It has been declared extinct. Never will we set eyes upon such a pulchritudinous bird. It was such a beautiful bird, indeed full of pulchritude, it was heavenly, paradisiacal, in fact.

Burnett River, Queensland, 1922

Not quite extinct is another parrot, also known, until relatively recently, from the 1920s. There were occasional public claims of sightings of the ‘fat budgie’, as the Night parrot was unkindly called. They were usually met with eye-rolling or accusations of ‘stringing’, a claim by a twitcher of a rarity when

something more common was mis-identified. Twitchers are competitive birdwatchers, aiming to build their Life-list with every bird species they have seen. The bird world was agog when Australia’s ‘Wild Detective’, John Young, a bird guide from North Queensland, announced in May 2013 that he had photographs and call-recordings of the Night parrot, Pezoporus occidentalis. Dedicated twitchers, of which am one, would kill, almost literally, to have a Night parrot on their Life-list.

In fact, we had anticipated the rediscovery of the Night parrot and had been planning a trip to find one. For a year or two, we were organising a September 2013 trip to the Diamantina in far-west Queensland where John Young had made his momentous discovery.

We had scoured the old records for the distribution of the species and noted their preference for old-growth Triodia irritans or Porcupine grass, known colloquially as Spinifex. There is hardly more inhospitable country than this – almost endless heat-shimmering gibber interspersed with clumps of spinifex, the toughest, most-unwelcoming plant of the harshest inland.

The string of good rainfall years in the previous decade made it likely if there were birds out there, even in very small numbers, the good seasons should have allowed increases in populations. We thought that we should go looking.

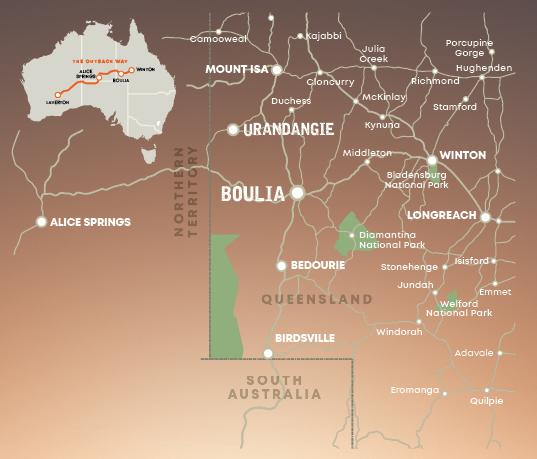

We started our research. The SA Ornithologist magazine in 1931 carried an article in which Night parrots were described as ‘fairly numerous’ south-east of Oodnadatta. There were further descriptions of where birds had been found, of their behaviour and nests and eggs. My oological passions had long subsided, it was the distribution that was of interest. I spoke with Wayne Longmore who was involved in 1990 with Walter Boles in the Australian Museum trip that quite fortuitously stopped on the roadside just out of Boulia in north-west Queensland. There on the ground beside the vehicle was the headless, desiccated body of a … Night parrot. Was it struck there by a car some time ago or was it struck elsewhere and carried by a vehicle, only to fall off in that spot?

I spoke with Angus Emmot a conservationist grazier out of Longreach and on whose kitchen table the specimen was placed while the museum researchers discussed with Angus the likelihood of more (and living) birds out there. I checked for the location of ‘roo shooter ‘Shorty’ Cupitt’s finding in 1993 of another decapitated bird. Do night parrots have heads at all? This bird was tangled in a fence, also not too distant from Boulia.

I visited the Birds Australia library and tracked down the 1993 issue of Emu (2) for the article on reports of 7 Night parrot sightings in north-west Queensland. I visited Melbourne Museum and was taken up to the bird collection to see two study skins that are in the collection. I figured it would help to know what the bird looked like. The somewhat offhand description of the Night parrot as a ‘fat budgie’ needed to be checked out.

My birdwatcher mates and would be fellow travellers lived in Melbourne, in regional Victoria, in South Australia and in Queensland. So we set to plan. We organised evening meetings to plan. We conducted phone meetings to plan. We sent around detailed emails to plan. We shared our research, we plotted routes, we allocated tasks and we discussed who would bring what. The timetable called for a September departure to meet in Longreach, travel via Winton, Larks Quarry and to Diamantina Station. We would scout out likely-looking habitat and there set up camp for a few days, spend the days striding through the Triodia country and see what we could flush and then the nights spotlighting to see what we could see.

Then the news broke – John Young had confirmed photos of a Night parrot. The location was given as a station in the Diamantina region with the precise details kept secret. We weren’t the only birdos who would kill to see a Night parrot and the fear was that the Night parrot would be killed through hounding by the deluge of obsessive twitchers.

We swallowed every detail of John Young’s search. He spent countless nights awake in the wee small hours with ears cocked for a different call to any he had heard before. He scoured the nests of Zebra finches and Fairy martins to see if any Night parrot feathers might have been used in the lining. He reckoned that his search took an aggregate of 17,000 hours before that wondrous late night in May. He described trembling with excitement when he first heard the call and then photographed the fat budgie scurrying mammal-like between clumps of Triodia. The video footage he took was the mainstay of the program of presentations he gave around the country. I attended one in Cairns some three years later and I was excited just to be there.

We went ahead with our trip 4 months after his rediscovery. We met up at a motel in Longreach where we had an excitable feast and too many drinks. We travelled in convoy to Winton which was in the grip of the Outback Festival. The cow-pat throwing was a highlight. We camped in the prickly scrub out of Winton near a muddy dam. In the predawn, the eyes of the coursing Spotted nightjars that criss-crossed above the water were as lit as twin-spotlights.

We traversed endless kilometres of gibber country where birds were particularly scarce. We stopped at Diamantina Station, now national park headquarters, and marvelled at the fortitude of the people who has kept it as a working station over the years. The summer heat would have been breathtaking – and the summers there last for months.

We arrived at Boulia and argued as to whether we should head, north, east or south to keep looking. We went east and found nothing and it probably didn’t matter in which direction we went. We didn’t come within a bull’s roar of a Night parrot.

The research we had done, significant in our minds, was as nothing to 17,000 hours of relentless searching. And where John Young had put himself in the mind of the bird as his approach, we had taken a boy’s own adventure approach to the exercise. In short, we played at searching for a Night parrot, he had worked at it. Our tens of hours constituted slothful dreaming while John Young had taken the path to fame that was lit by midnight oil. And fame he found. He will forever be known as the fellow who found the Night parrot.

But his subsequent work has stunned, provoked and mystified. He certainly did find, after around ninety years, the long-lost Night parrot. But were his photos doctored as is claimed? Was the nest he said he found fair dinkum? Were they real eggs? He has previously been suspected of chicanery. He claimed a new species of parrot, a Blue-fronted fig parrot with a photograph as evidence. Expert analysis of the photograph led to suspicions that aspects of the bird’s plumage had been altered, changing its brow from red to blue. Penny Olsen’s book Night Parrot gives chapter and verse of the range of matters.

In a blog (4) maintained by Greg Roberts of Queensland’s Sunshine Coast , a discussion of John Young’s find, and of the doubts that surround some of his previous work, is discussed. There appears to be no explanation for his claims and behaviour. There are even questions regarding his photos of the Night parrot ranging from enhancement to doctoring.

With slurs on his integrity already in the public domain, why would he so risk his reputation further when it was already assured with the single undoubtable act of the rediscovery of the feared-extinct Night parrot? It was a feat worthy of the highest praise, as were the lengths to which he went to make the discovery. Balance that with the inability to cooperate with seemingly anyone in subsequent research and management for Night parrots is confounding and you have a highly perplexing character. He has ‘been let go’ by more than one organisation that enlisted him in their conservation work.

A collection of articles from public sources has been compiled and can be found at greghunt.net/category/birds/night-parrots/ . Here you will find details and questions regarding the discoveries and the strange behaviour of John Young, Australia’s ‘Wild Detective’.

References

1 Geopsittacus occidentalis, The SA Ornithologist, July 1, 1931 (pp 99 70),

J Neil McGilp

2 Notes on Live Night Parrot Sightings in North West Queensland, Stephen

Garnett et al, EMU Vol 93, 1993, pp 292 – 296

3 Night Parrot: Australia’s Most Elusive Bird, Penny Olsen CSIRO Publishing,

Melbourne, 2018.

4 Natural history blog by Greg Roberts, Sunshine Coast, Australia

http:/ sunshinecoastbirds.blogspot.com /2013/07/john-young-and-

paradise-parrot.html